Rice: its Popularity & Process

Why is Rice So Popular?

Rice has a very long and simple history and one of the main reasons behind its near-ubiquity as a staple food is its Adaptability as a crop: DIFFERENT VARIETIES can be grown in most areas that can thrive in tropical or temperate environments, with extensive irrigation. But besides adaptability, there is one more important aspect that explains its Popularity: TASTE. History shows that people all over the world come to love the taste of rice, and not just any variety. Technological inventions hardly influenced the taste buds of any people regarding rice.

For example, when Champa rice, an early-ripening and drought-resistant variety that would eventually change the nature of rice cultivation worldwide, was introduced to China in the 11th century by the Emperor Zhenzong of the Song dynasty, many farmers adopted it to more easily pay for their rice tax to the government, even though an older variety of rice was far more prized. In response, the government decreed that Champa rice could be used to pay the rice tax only with an additional 10% surcharge. For example, when Champa rice, an early-ripening and drought-resistant variety that would eventually change the nature of rice cultivation worldwide, was introduced to China in the 11th century by the Emperor Zhenzong of the Song dynasty, many farmers adopted it to more easily pay for their rice tax to the government, even though an older variety of rice was far more prized. In response, the government decreed that Champa rice could be used to pay the rice tax only with an additional 10% surcharge.

Similar challenges emerged during the 1960s Green Revolution or the Third Agricultural Revolution; this is when initiatives resulted in adopting new technologies, including high-yield varieties of cereals, especially dwarf wheat and rice. Great Leap Forward in the world; and, even more recently, with efforts like the Golden Rice Project, a variety of Oryza sativa plant species rice produced through genetic engineering to biosynthesize beta-carotene with the hope of addressing the problem of micronutrient deficiency particularly to address the issues like vitamin A deficiency. In each of these examples, agricultural advancements were designed to increase rice yields but still, the fact remains that rice is not just a single, fungible commodity rather it is a class of commodity that is made up of lots of varieties, each of which has a specific market due to behavioral, cultural and taste preferences.

SIMPLE MINDSET: rice eating People consider rice as their daily diet preference, and it can be very difficult to convince them to change their minds, even if they are provided with more economical or more nutritious options.

Norman Ernest Borlaug: Father of the Green Revolution

How Rice is Processed and Sold?

Aside from the different types of rice out there, which are the products of generations of crop selection, almost every rice can be classified by how much it has been processed.

Before going ahead, we should know What is Rice?

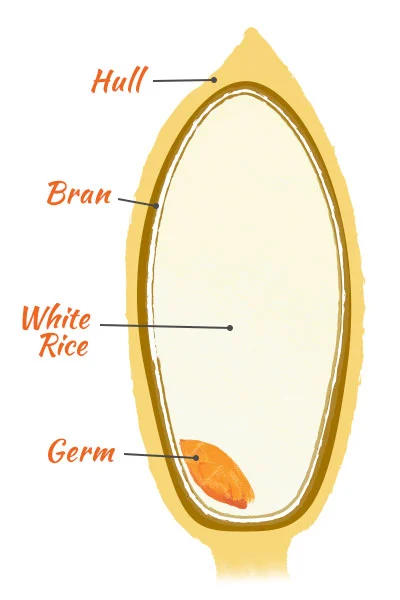

Rice, just like other grains, is the edible seed of grass. The most familiar rice variety in the world comes from Oryza sativa or commonly known as Asian rice. Each grain, or seed, of rice contains:

- A tough outer hull – also known as the husk, the hull needs to be removed before it can be eaten. The hull is removed in every variety of rice.

- Bran – Under the hull, the bran layer is not removed in all rice types. This nutritious whole grain section is usually tan-colored, but it may be reddish or black depending on the pigmentation in the bran layers. The bran layer may be consumed, but it is often removed when further processing rice.

- Endosperm (also known simply as white rice) – What remains once the outer hull and bran layers are stripped away. Though this is the most commonly consumed part of rice, it is also the least nutritious.

- Germ – Found under the hull, the germ is not a layer, but a small kernel. It is nutrient-dense and packed full of B vitamins, minerals, and proteins, and contributes to the overall color of rice.

As Harold James McGee, an American author who writes about the chemistry and history of food science and cooking explains in his famous seminal book, On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen (first published in 1984 and revised in 2004), the very nature of how we tend to consume rice adds to the cost of its production: “Because rice is usually consumed as individual grains and not as meal or flour, rice milling is much more involved than the grind-and-sieve approach taken to wheat or corn.” In other words, because it won’t be ground to oblivion, like wheat or corn, rice requires more careful handling to preserve its grains. Also, unlike wheat, rye, and maize, rice has a husk (much like barley and oats), which must be removed before further processing, adding another step.

After a grain of rice is husked, what remains is what we call Brown rice, an intact kernel that is still covered with layers of bran. Typically, the layers of bran and the germ will be abraded off the kernel, which is then polished to remove the aleurone layer, a very thin layer of oil, minerals, protein, and vitamins. Now typically after stripping off the hull, bran, and germ the leftover remains are just the endosperm, i.e., White rice or may be known as polished rice. You can purchase almost every variety of rice in its brown, mostly unprocessed state, or in its polished form. Brown rice generally requires more water and more time to cook, due to the extra layer of bran and is full of nutrients. But there is much “converted” rice that has been Parboiled with its husk on, then dried and processed. Converted rice has a greater nutritional value and an improved shelf life. Finally, there is some vitamin-enriched fortified rice on the market.

Speaking of rinsing rice, it’s always better to rinse your rice before cooking! Rinsing removes excess starch on the exterior of the grains, which can make cooked rice unappealingly gummy.